Roy Thomson Hall Site Analysis

Location: Roy Thomson Hall

Address: 60 Simcoe St, Toronto, ON M5J 2H5

Date: December 5, 2013

Roy Thomson Hall is a unique 2,630-seat Toronto concert hall that lies in the heart of the entertainment district. It is managed by The Corporation of Massey Hall and Roy Thomson Hall. It was completed in 1982 and it has quickly become one of Toronto’s go to venues. With its diverse programming, Roy Thomson Hall wants to become a home for all.

Site Analysis: Historical Research

While we walk along the busy streets going on with our daily lives, we tend to be uninterested in the history of the locations in which our buildings are situated. Long before the Roy Thomson Hall became what we know it as today, there is a rich history starting from the early 1800s that can be traced back from the King St. West and Simcoe area.

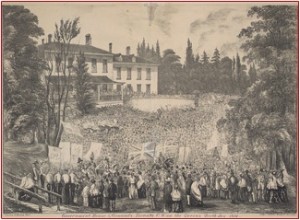

From 1798 to 1802, the King St. West and Simcoe area was originally the home of Chief Justice John Elmsley, often called the “Elmsley’s House” (Littler and Terauds 17). From 1815 onwards until the 1860s, it served as the Government House. Below are two pictures of the Government House. The first one dates back to 1834 and the second one was in 1854, where the Torontonians can be seen celebrating the Queen’s birthday (Littler and Terauds 17).

It was not until 1845 where Toronto develop its own formal music society, where the need for an auditorium of sufficient size emerged, making St. Lawrence Hall on King Street East the first permanent home for music in Toronto (Littler and Terauds 11). After many decades, several other venues were built in order to house the growing number of communities, marking the thriving of the music community in Toronto.

( Courtsey of the Toronto Public Library)

Lithograph by Lucius O’Brien, 1854. From Toronto Public Library, Toronto Reference Library, Special Collections (T 11870)

In order to understand Roy Thomson Hall’s history, it is important to look at its sister building: Massey Hall which opened in 1894, and it was considered Toronto’s “musical crown jewel” along with being one of North America’s finest music venues of the time (Littler and Terauds 14). Taken from the Massey Hall’s website, its “intention was the auditorium [that] would aid in the development of the arts and would be “spacious, substantial and comfortable, where public meetings, conventions, musical and other entertainments, etc., could be given”” (“Massey Hall: Historical Timeline”). Its acoustics were put to the test in 1961 by a European physicists, Professor Fritz Winckel of Berlin, impressing him as he claimed that Massey Hall was one of the world’s finest (Littler and Terauds 20). It soon became the home of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra (formerly known as New Symphony Orchestra) and the Toronto Mendelssohn Choir (“Massey Hall: Historical Timeline”). As years went by, Massey Hall’s building started to deteriorate physically and acoustically. Calls have been made for either refurbishment, renovation, or replace the building entirely (Littler and Terauds 27). Thus, in 1967, a new concert hall was announced to replace Massey Hall (“Roy Thomson Hall – Historical Timeline and Roy Thomson Hall: A Portrait.”).

Due to public backlash of planning to replace the Massey Hall with the new one, Edward Pickering, President of the Toronto Symphony and his building committee had to look for a different location. As Pickering and his group did not get their preferred locations, they approached the City of Toronto for advice (Littler and Terauds 31). After two years of considerations and meetings, the City of Toronto made negotiations with the Canadian National and Canadian Pacific Railroads for the new concert hall to be built at the southwest corner of King St. West and Simcoe St, making the area extremely accessible via public transportation (Littler and Terauds 32-33). The building committee sought out Canadian architect Arthur Erickson and acoustician Theodore Schultz to design the new venue, reflecting the amount of ambition and hope they envisioned for this new concert hall (Wardrop). The new concert venue was made of concrete, steel and glass. The initial budget proposed for the building in 1967 was approimately $10 million, but by 1981, the total cost of the building went up to $44 million, making this “the largest amount of money that had ever been raised from the private sector in Canada for a cultural project,” (Littler and Terauds 39). The new building was known as the New Massey Hall until January 13, 1982, when they changed the venue name to Roy Thomson Hall as the Thomson family donated $4.5 million to the project (Kraglund).

Roy Thomson Hall officially opened on September 13, 1982 with performances from Toronto Symphony Orchestra and the Toronto Mendelssohn Choir (“Roy Thomson Hall – Historical Timeline and Roy Thomson Hall: A Portrait.”). From September 14 to 18, 1982, there were various performances by Anne Murray, the Canadian Brass, Lois Marshall, Gordon Lightfoot, the Canadian Children’s Opera Chorus and more to celebrate Roy Thomson’s Hall opening. In 1983, The Hall gained a national segment on CBC Stereo’s that broadcasted 35 concerts every Sunday afternoon (“Roy Thomson Hall – Historical Timeline and Roy Thomson Hall: A Portrait.”). However, in 1984, Roy Thomson Hall suffered significant financial losses, President Edward Pickering revealed a more diverse programming for the venue, ranging from jazz, classical music, pop, and so on in order to mirror Toronto’s diverse audiences, styles and cultures (“Roy Thomson Hall – Historical Timeline and Roy Thomson Hall: A Portrait.”).

In 2002, Roy Thomson Hall underwent a 22-week renovation, costing roughly around $20 million (“Globe and Mail (1936-Current)” P12). The main goal of the renovation was to improve its “cold” acoustics seeing as the thin walls are leaking the sounds (“Globe and Mail (1936-Current)” P12). The renovation would change the Roy Thomson Hall visually and acoustically, by using hand selected light hardwood by acousticians to cover much of the concrete surface inside the hall (“Globe and Mail (1936-Current)” P12). The light hardwood would serve as a dual function: the first and foremost is to properly reflect the sounds in the hall and drastically improve its acoustics, and the second function was to make the Roy Thomson Hall look more visually stunning (“Globe and Mail (1936-Current)” C6). No other major changes were made to the Roy Thomson Hall after this renovation, aside from the addition of the following lounges: the donor lounge (2004), The Marquee Club and Maestro’s Club Lounge (for members only, since 2004), and The American Express Lounge (2013) (“Roy Thomson Hall – Historical Timeline and Roy Thomson Hall: A Portrait.”).

Site Analysis: On-site Research of Roy Thomson Hall

I have never been to the Roy Thomson Hall before this assignment, but as soon as I arrived there, I can immediately see why it has quickly become one of Toronto’s landmarks since it was built. I can also see several concepts that we have discussed in class that can be applied to the Roy Thomson Hall.

In Cohen’s Sounding Out the City: Music and the Sensuous Production of Place, she argued that “music and place [are] not as fixed and bounded texts or things, but as social practice involving relations between people, musical sounds, images and artifacts, and the material environment” (276). Although Cohen connected this argument in relation to the Jewish community in Liverpool and Brownlow Hill, the idea can still be seen in the context of Roy Thomson Hall in Toronto. While the Roy Thomson Hall does not play a role in defining a specific ethnicity in Toronto, it does define Toronto’s community and Canada’s community as a whole. An example that illustrates this argument is the display of Glenn Gould’s Piano in Roy Thomson Hall’s lobby. Glenn Gould was born on September 25, 1932 and died on Oct 4, 1982, and he was a famous Canadian pianist known for his interpretation of Bach’s music and his unorthodox performances (Beckwith, Bazzana, and Payzant ). In one of the interviews I conducted, I asked Stephen, an employee at the Roy Thomson Hall, about the purpose of displaying one of Gould’s pianos. He replied “Roy Thomson Hall is very fortunate to have the Glenn Gould Piano to be displayed as an artifact. By having one of his pianos, it serves as an enhancement of the experience here at the Roy Thomson Hall. When the audience starts filling the hall before the show and see the piano, we want them to think ‘Wow, I can expect a lot and still know that I am getting the best experience here as possible.’ The display also celebrates and honours one of Canada’s best and famous pianist, and I think that paying homage to our own musicians is important” (McGrath). Here, we can still the relationship between people, place and the artifact in the material environment.

Another argument of Cohen’s that can be seen at the Roy Thomson Hall is that “music acts as a focus or frame for social gatherings, special occasions, and celebrations…and involves everyday social interactions…to establish, maintain, and transform social relations” (287) and “although music is part of everyday life, it can also be perceived as something special, something different from everyday experience” (285). Thanks to the hall’s design by Arthur Erickson, Roy Thomson Hall is adaptable to all sorts of special events. While the hall is generally for music showings, Roy Thomson Hall does serve other purposes as well. Another person that I interviewed, Chloe, a mother that has been to the Roy Thomson Hall multiple times expressed her experience there. To Chloe, the Roy Thomson Hall “is a great place for meeting people. It’s nice to be around people who share the same musical interests as you and no one there judges you. [She] has made friends from different shows that [she] still keeps in touch with today” (Skyday). Another interviewee shared the same sentiments as Chloe. Justin happily told me his experience at the Roy Thomson Hall, saying that “[he] usually listens to classical music every day, but it is also nice to dress up and go out to sometime to actually hear it live. Even though this is once in a long time for [him], the change in atmosphere of everyday life is a good thing,” (M.) Stephen informed me that that the Roy Thomson Hall has Christmas shows, the African Canadian awards along with the SoCan awards are held at the Hall, they do stand up comedy, have speeches, and TIFF (Toronto International Film Festivals) holds screenings at the Hall as well (McGrath). Stephen also said that there are instances where people book the Hall (or parts of the Hall) for parties and weddings (McGrath). The belated Jack Layton’s funeral was held at the Hall as well (McGrath).

One of Justin’s answers greatly reflects Christopher Small’s notion of musicking. According to Small, musicking is “an activity in which all those present are involved and for whose nature and quality, success or failure, everyone present bears some responsibility,” (Small 10). While describing his experiences at the Hall and one of the reasons why he goes there, he explains to me that “overall, [his] experiences at the Hall are very memorable because hearing the music and the audience in person is better, just like watching sports in person. There is also a chance for an encore performance by the musicians if there was enough applause from the audience, something that you can’t be a part of in the same way by watching the performance on TV or listening to the radio,” (M.). Here, we can say that the audience is part of the musicking process just as such as the performer(s) putting on the show. If there were not enough applause, then there would be no encore. I would say the people watching the performance on TV or listening to the radio are not part of the musicking since their participation does not contribute nor affect the outcome of the show, whereas the live audience, along with the the staff and crew can make or break the show.

Hebdige’s idea of subcultures can also be applied in the context of Roy Thomson Hall. In his article, he looked at how different subcultures have their own styles, symbols and even to a certain extent, their own political beliefs (Hebdige 63). He specifically studied the Punk subculture and his conclusions demonstrated how certain groups tie their values and practices together. In the case of Roy Thomson Hall, seeing as they widened their programmes in order to reach out to more audiences, it can be seen that certain musical programmes would appeal to certain subcultures that enjoy that specific type of music whereas other types would put some audiences off. My question to Stephen was “while there are no dress codes at the Roy Thomson Hall, do you notice any trends that are particular/specific to certain audiences in relation to musical genres?” His response to the question is as follows: “Yes, as I believe the knowledge of dress codes that people have are inherent in the culture. Audiences for the classical music programmes do dress up as a fancy evening out. I guess for them, it makes the performance feel more high-class or exclusive. The audiences for classical music shows tend to be more on the adult side, although it is uncommon to see young children and teenagers attending these shows. For other programs, such as pop shows, the teenagers would be in jeans and T-shirts, similar to how we are dressed right now” (McGrath). Although audiences of certain genres do not always conform or follow their subculture’s practices, based on Stephen’s answers however, the classical music genre and pop music genre do tend to follow said practices.

Interpretation of Space

As stated earlier, the Roy Thomson Hall is very adaptable, therefore its physical, media and musical factors changes depending on the type of programming that it is being presented. Both of Schafer’s concept of hi-fi and lo-fi can be applied to the Roy Thomson Hall. According to Schafer, “the higher the differentiation between signal and noise, the easier it is to distinguish between what is “information” and what is not” (Kelman 216). The lobby and ticketing area would be considered lo-fi, as there are multiple sounds that are constantly being heard, but once we get inside the auditorium, it becomes a hi-fi soundscape as “discrete sounds can be heard clearly because of the low ambient noise level,” (Kelman 216). During my first visit to the Hall, I was sitting in the audience (main level) listening to the Toronto Symphony Orchestra practice (there were only about 5-7 other people aside from Stephen and I), however I can hear the director whispering to someone next to him clearly, and they were on the opposite side of the room.

I do not have a picture of the stage seeing as they were practicing all 3 times that I went, and I did not have their consent. However, the stage itself dimensions of the stage are: “45-feet wide upstage, 62-feet wide downstage, 82-feet wide downstage, full apron, 41-feet deep at centre and 28-feet height clearance” (“Roy Thomson Hall – Production and Technical”). The following pictures are taken with the written consent from Stephen.

The spotlights on the ceiling changes angles depending on the programme. Usually for classical symphonies, it remains the same seen in the picture, however, if it is a soloist or award shows, only the spotlights on hanging from the bar are on (McGrath). The canopy lowers if it is a soloist in order to better reflect the sound, and lowers if it is during a screening for TIFF (McGrath).

The wood, as mentioned above, was hand-selected by top acousticians to reflect the sounds (“Globe and Mail (1936-Current)” P12). The panels can lower, but again, it would depend on the program. The panels can be covered with a black cloth, especially during the TIFF screenings so the panels will not reflect the lights. It can also be seen in these two pictures that there are extra spotlights at the back on the third floor, and that there are lights embedded into the ceilings (McGrath). I have circled the speakers that are attached to the ceiling (McGrath). These speakers would be on during pop programmes, award shows, TIFF screenings, stand up comedies, and so on (McGrath). The classical symphonies and operas are unamplified (McGrath).

From what I have learned about the Roy Thomson Hall, I am quite impressed. The first time I visited, the circular design of the building along with the spacious lobby forming a continuous loop around the auditorium made me interested in the site (I do not go to downtown often, and have never been to the King and Simcoe area). Its interior reflective nature is to bounce the light off from the sun and buildings, and Stephen told me that Arthur designed Roy Thomson Hall the way it is so that the colour comes from the music and people, creating a combination from the outside life and the one inside (McGrath). This also relates to the notion of people, music and place having an influence over together other. I can now see why the Roy Thomson Hall is unique to Toronto and as Stephen puts the Hall as “one of Toronto’s epic experiences,” (McGrath). I would definitely want to watch a performance at the Roy Thomson Hall!

Works Cited

“Audibly yours, at Roy Thomson Hall.” Globe and Mail (1936-Current) [Toronto] 19 April 2001, P12. Web.

24 Nov. 2013. <http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.library.yorku.ca/hnptorontostar /docview/1125756362/1422532230471CD4BD8/3?accountid=15182>.

A.Y, Kelman. ” Rethinking the Soundscape: A Critical Genealogy of a Key Term in Sounds Studies.” Senses and Society. 5.2 (2010): 212-234. Print.

Beckwith, John, Kevin Bazzana, and Geoffrey Payzant. “Glenn Gould.” 2013. <http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/glenn-gould-emc/>.

Cohen, Sara. “Sounding Out the City: Music and the Sensuous Production of Place.” Trans. Array The Place of Music. New York: The Guilford Press, 1998. 269-290. Web. 26 Nov. 2013. <http://popmusic.info.yorku.ca/files/2013/10/Cohen-Production-of-Place.pdf>.

Harris, Jane. Government House (1815-1860), Simcoe St., s.w. cor. King St. W.. N.d. Photograph. Toronto Public Library , Toronto. Web. 23 Nov 2013. <http://www.torontopubliclibrary.ca/detail.jsp?R=DC-PICTURES-R-1749>.

Hebdige, Dick. “Style as Homology and Signifying Practice.” Trans. Array Subculture: The Meaning of Style. London: Routledge, 1979. 56-65. Print.

Kraglund, John. “Concert Hall Renamed After Roy H. Thomson.” The Globe and Mail: 0. Jan 13 1982. ProQuest. Web. 21 Nov. 2013.

Littler, William, and John Terauds. Roy Thomson Hall: A Portrait . Canada: Dundurn, 2013. Print.

“Massey Hall: Historical Timeline.” Massey Hall. The Corporation of Massey Hall and Roy Thomson Hall. Web. 25 Nov 2013. <http://www.masseyhall.com/mh_history>.

M., Justin. Personal Interview. 24 Nov 2013.

McGrath, Stephen. Personal Interview. 27 Nov 2013.

O’Brien, Lucius. Government House & Grounds, Toronto C.W. on the Queen’s Birth-day, 1854. 1854. Lithograph. Toronto Public Library, Toronto. Web. 23 Nov 2013. <http://ve.torontopubliclibrary.ca/ktr/map1858/thenandnow/governorhouse.html>.

“Roy Thomson Hall Gets Make-over.” Globe and Mail (1936-Current) [Toronto] 19 Sept 2001, C6. Web. 24 Nov. 2013. <http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.library.yorku.ca/hnptorontostar/docview /1125613943/1422532230471CD4BD8/2?accountid=15182>.

“Roy Thomson Hall – Historical Timeline and Roy Thomson Hall: A Portrait .” Roy Thomson Hall. The Corporation of Massey Hall and Roy Thomson Hall. Web. 25 Nov 2013. <http://www.masseyhall.com/rth_history>.

“Roy Thomson Hall – Production and Technical.” Massey Hall. The Corporation of Massey Hall and Roy Thomson Hall. Web. 30 Nov 2013. <http://www.masseyhall.com/rent_rth_productiontechnical>.

Skyday, Chloe. Personal Interview. 30 Nov 2013.

Small, Christopher. “Prelude: Music and Musicking.” Musicking: The Meanings of Performing and Listening. Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, 1998. 1-18.

Wardrop, Patricia. “Roy Thomson Hall.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. 2013. <http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/en/article/roy-thomson-hall-emc/>.