Site Analysis: The Legendary Horseshoe Tavern

Site Analysis of The Horseshoe Tavern

Location

The Horseshoe Tavern, also known as the Shoe, is a bar/music venue located at 370 Queen Street West (e.g. see fig. 1).

Figure 1

Figure 1

History

The Horseshoe Tavern’s website shares an in-depth history of the early years of the business, including the talents who have performed at the venue, the change in ownership over the years as well as its failures and successes. The website states that in November 1947, Jack Starr, shown in figure 2, purchased the building at 368-370 Queen Street West. The venue was initially opened as a “restaurant-tavern”, offering music on the side (Our History).

Figure 2

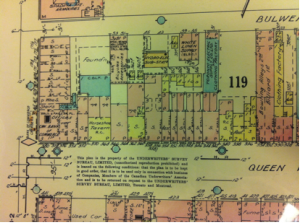

The building was established in 1861. According to the fire insurance plan of 1954 (e.g. see fig. 3), the building shared the lot numbers 368 and 370. The Toronto Directory 1861 indicates that the building housed an Engineer, a Blacksmith, and two Butchers at that time (79). Ownership of the building frequently changed until 1947, when the Horseshoe Tavern opened. Beginning in 1862-1863, the building 368-370 was mainly occupied by commercial businesses such as a grocer, a machinist, and a butcher (Toronto Directory 1862-1863, 207). In 1929, the building was vacant for a year and in 1933, the building was converted into Frank’s Clothing and Footwear (Toronto Directory 1929, 1657). In 1940, Warren Drug Co. Ltd acquired the building at 370 and owned it until 1947 (Toronto Directory 1940, 391), when Jack Starr took over ownership. According to The Horseshoe Tavern’s website, the new provincial liquor license laws (circa 1947), permitted Starr to convert the commercial property to an “eatery-tavern” and start serving alcohol. The Shoe had a legal capacity of 87 seats (Our History), however, in The Globe and Mail, Dick Brown states that the venue grew to seat 400. Currently, the venue’s capacity is 490 seats.

Figure 3

Brown also indicates that The Shoe offered a wide array of music, however once Jack Starr realized that country music drew in the most crowds, he focused on that genre (The Globe and Mail, A33). The first act to play at the tavern was ‘Marvin Rainwater’ and the first country performer was a man by the name of Shorty Warren. Starr also notes that country music was not a socially accepted genre at the time, so the tavern provided an escape for the country music lovers (The Globe and Mail, A33).

In “Punks Against Police at the Horseshoe Tavern”, Nicholas Jennings claims that in the first few years, the tavern had a bad reputation because Edwin Alonzo Boyd, a legendary bank robber, became a regular customer. As a result, the media did not focus on the bar’s music, but on the notorious client it served (1). Its reputation eventually changed in the mid-50s when Starr converted the bar into a live music venue seating almost 500 people (Our History). In the following 25 years, the Shoe housed numerous country acts including Willie Nelson, Conway Twitty, Waylon Jennings, and Ian & Sylvia Tyson etc (Jennings, 1). Canadian country legends such as Stompin’ Tom Connors brought fame to the place because Starr had begun to promote Canadian talent in the 1960s, which still remains the Horseshoe’s goal to this day. In 1976, Jack retired and sold the business (while retaining ownership of the building) to music promoters, Gary Cormier and Gary Topp, also known as ‘The Garys”(Our History). Alan Carter et al.’s Global News footage, The Shoe, relates that the Garys were motivated to revive the music scene as country music started to wane. In the footage, Gary Topp explains that the change was happening in a “stale and staid city”(The Shoe, Global News). Thus, with the Garys came new waves of music including avant-garde jazz, rock, reggae, African rhythm and blues, punk, and folk (The Shoe, Global News). The Garys wanted to see all kinds of performances and the range of music they brought in reflected their non-discriminatory nature. In 1978, a notable band, The Police, performed at the Tavern before they went on to become Grammy award winners. That same year, the Garys were asked to leave, so they hosted a punk show called “The Last Pogo” as a tribute to their past success. The show featured Teenage Head, the Vilestones, Cardboard Brains and other punk bands. The number of people at this event went beyond the maximum capacity and when the police tried to shut down the event, a riot broke out causing major damage to the building (The Shoe, Global News). Jennings states that “the destruction that ensued left the club’s tables and chairs shattered, all of it captured on film which was turned into a documentary called The Last Pogo (“Punks Against Police at the Horseshoe Tavern”, 1). After the riot, the bar sustained major financial problems (Our History). The bar was divided into three retail spaces. The Shoe changed its name to Stagger Lee’s and in the early 80s, the bar reopened as a 1950s strip club (The Shoe, Global News). Will, my interviewee, who has frequented the Horseshoe since the 80s, described the area at that time as “ rough around the edges” and “down and dirty urban”.

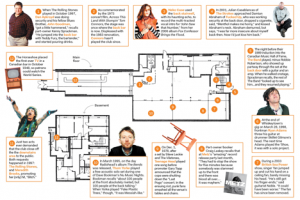

Because of the tavern’s hardships, Jack Starr came out of retirement in 1982 and employed X-Ray Macrae, Dan Akroyd, and Richard Crook to run the business for him. The collaboration of these three men changed the reputation of the Shoe and turned it into a popular place to listen to music (Our History). Ken Sprackman was another important addition. He joined the threesome in 1983 and began to change the layout of the venue by moving the stage from the centre to the back of the bar, splitting the space into two sections. The venue now has a back and front bar. The live music space was reduced to a quarter of its original size, thus creating a small live music venue (Our History). Will recounted that ‘Queen Street started to take off with art galleries, music culture, and hipsters’ attracting a better clientele.

Also, the new leaders focused on Starr’s initial motives, that was, to promote up and coming local talent. In doing so, the Shoe embraced a wider variety of music by showcasing local performers such as Handsome Ned, The Bopcats, Prairie Oyster, and other bands. The renovations, as well as the wide variety of music including country, blues, alternative, and punk, are what shaped the Shoe and established its reputation (Our History). In the early 1990s, the popularity of rock began to die off at the Shoe and the business began to suffer because of the recession (Our History). As a result, in 1995, X-Ray Macrae stepped aside and hired Jeff Cohen to book new emerging rock and folk bands such The Bare Naked Ladies, the Waltons, Lowest of the Low, and Great Big Sea etc. Also, Cohen and his assistant Craig introduced “a new business model for booking club venues in Canada”(Our History). The pair created ‘Against the Grain Concerts’ (ATG) and began to promote bands outside of the venue. ATG advertised the Horseshoe as more of a concert venue than a tavern. Advance tickets were made available for shows at the venue and key renovations were made such as raising the stage, opening up walls to create better sight lines and building seating on the east side of the venue (Our History).

As of today, the Horseshoe plays alternative rock as well as other music five days a week with three to five bands per night. Rich, once a regular patron and now a day bartender of 12 years, remarked that the area has become much more gentrified. Queen Street West is filled with retail spaces such as American Apparel and H & M. A & W, with a fast -food restaurant on the west side of the Shoe and a mobile store is on the east side. A decade ago, Rich mentioned that the neighbourhood had more bars and restaurants, however now, “the places are being pushed down by rent”. In other words, it is more challenging for a restaurant or a bar to survive these days due to more costly leases. When high-end stores move in, the rent rises.

Description

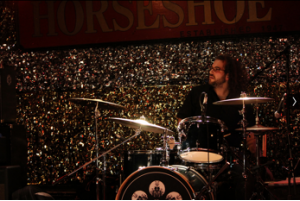

The Horseshoe Tavern’s décor is unpolished, old-fashioned and “looks like a dive”, as Will remarked, with marked flooring and memorabilia covering its walls. The east wall is decorated with newspaper clippings, pictures of past performers as well as past owners. As one of the oldest live music venues in Toronto, these elements add to the tavern’s history, authenticity and appeal. The staff at the Horseshoe is another part of its attraction. Both Duncan and Will, two regular patrons I interviewed, frequent the tavern to socialize with others, but more significantly, to be a part of the tavern’s “extended family”, as Duncan stated. Duncan spends his time at the Shoe shooting pool, socializing with other regulars, drinking, and enjoying the music. He mainly stays in the front bar, as the area is conducive to these activities whereas the back bar is primarily used to attend performances. The floor plan shows the divide between both spaces (e.g. see fig. 4). The front bar is significantly smaller than the back, where the stage is set up. The back bar has about 15 long narrow bar-like tables that fit nothing more than a drink. Benches line the east wall. The stage is small with a checkered dance floor in front, and a tacky background resembling silver confetti (e.g. see fig. 5).

Figure 4

Figure 5

Analysis

Not only do the two spaces in the venue distinguish particular activities, but they also divide people according to musical taste. In Systems of Articulation, Logics of Change: Communities and Scenes in Pop Music, Will Straw indicates that “… particular social differences are articulated within the building of audience around particular coalitions of musical form”(384). For example, Duncan’s taste in music includes house and disco, which often differs from the genres performed in the back bar, therefore, his choice of space reflects his and others’ musical preferences. The individuals who stay in the front and those who prefer the back bar are revealing their social preferences, whether that means listening to music or conversing with other patrons. In addition, Ted, a nighttime employee who has been bartending in both the front and back bar for 27 years, stated that two types of people attend the tavern: those who enjoy the music and those who come to enjoy the staff and the social lifestyle. Duncan and Will, both of whom stay primarily at the front bar to socialize, reaffirmed this statement. Duncan also stated that when a band is performing, it creates a different kind of atmosphere. A flow of people walking through the front bar to reach the back creates more ambience in the space because of the larger volume of people. The opportunity to eaves drop on people’s conversations becomes a ‘source of entertainment’ as Duncan put it. Despite the fact that the venue is divided into two spaces, a constant flow of people come and go from the back to the front (especially because pints are only served at the front bar).

In the back bar, the sound is loud and clear. The experience is more about appreciating and bonding over a musical performance than it is about socializing with other regulars or bartenders because it is too loud to have a meaningful conversation. In addition, the main speakers are on the stage. Back speakers are only used when the area gets really busy and noisy. Lastly, the back bar is lit differently from the front bar. The latter is well lit, whereas the former is mostly dark, apart from the lights pointing to the stage and over the bar (e.g. see fig. 6). With lighting pointing to the stage, the performers are blinded and clearly displayed while the audience remains in the dark. In Sounding Out the City: Music and the Sensuous Production of Place, Sara Cohen discusses the influence music has on social relations and activities in certain places. She states, “…music is not represented and interpreted: it is also heard, felt, and experienced” (277). This applies to both the audience and the performers. While the audience absorbs the music, the performers also absorb the sounds from the audience and feed off of that energy to create a harmonious experience and an atmosphere of inclusion.

Figure 6

In Sara Cohen’s article Ethnography and Popular Music Studies, she states “the resulting representations of local music practices and sounds are compared and contrasted and related to the social, political and economic agendas of those promoting them”(129). These factors are present at the Horseshoe Tavern. Socially, the Shoe encourages a social and even familial lifestyle. The tavern is known as a tourist attraction because of its diversity, and as Will stated, because of its “international clientele”. On a cultural level, they value and promote Canadian music and artists. Jack Starr, the founder of the Shoe as well as consecutive owners have imported Canadian performers to enrich the community and provide opportunities for these bands. Interestingly, besides Canadian bands, the Shoe gave The Police a chance to play before they became popular (The Shoe, Global News). Also, the staff treats everyone equally. For example, in my interview with Duncan, he shared that “regulars are appreciated here” and “you get treated equally whether you have a ticket to listen to a band or not”. This exemplifies the non-discriminatory nature of the Shoe. Lastly, the venue provides an affordable experience for the ordinary citizen who enjoys music and social interaction. Customers do not have to pay to enter the front bar and drinks are reasonably priced. As Duncan mentioned, he stays at the front and can still enjoy the sounds from the back as do the other customers. To enter the back, it costs ten dollars, which is a small fee to hear big acts such as The Rolling Stones, who have popped into that venue to perform.

Finally, after researching the history of the Horseshoe Tavern, conducting interviews and performing an ethnographic research, I can conclude that the Shoe is a place where individuals can socialize and experience music as a group – a powerful experience when everyone is enjoying music together.

Works Cited

Brown, Dick. “The Horseshoe Tavern Had Faith”. The Globe and Mail (1936 –Current); Apr 14, 1973; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Globe and Mail (1844-2010). Pg. A33. Print.

Carter, Alan, Mia Sheldon, and Matt Lehner. “The Shoe”. 16×9. Global News. Toronto. 21 Jan. 2013. http://globalnews.ca/news/412825/the-shoe. Web.

Cohen, Sara. “Ethnography and Popular Music Studies”. Popular Music, 12.2 (May,1993): 123-138. Print

Cohen, Sara. “Sounding Out the City: Music and the Sensuous Production of Place” from The Place of Music, Leyshon, A., Matless, D., and Revill, G. (eds), New York: The Guilford Press, 1998. Print.

Duncan. Personal Interview. 20 Nov. 2013.

Figure 1. Horseshoe Tavern. maps.google.com. Web. 5 Dec. 2013

Figure 2. Toronto Star. (1969): 45. 22 Nov 2013. Print.

Figure 3. Fire Insurance Plan (1954): 79 (1). Print.

Figure 4. The Grid (2012). Web. 23 Nov. 2013.

Figure 5. “The Evelyn Room” Flickr.com. (2009). Web. 4 Dec. 2013.

Figure 6. “Paint” Flickr.com. (2013). Web. 4 Dec. 2013.

Jennings, Nicholas. “Punks Against Police at the Horshoe Tavern”. The Canadian Encyclpedia. Toronto Feature: Horseshoe Tavern. 20. Nov. 2013.

“Our History” The Legendary Horseshoe Tavern Bar & Music Venue Since 1947. http://www.horseshoetavern.com/our-history/. 20 Nov. 2013. Web.

Rich. Personal Interview. 20 Nov. 2013.

Schafer, R. Murray. “Introduction” from The Soundscape. 3-12. Print.

Sterne, Jonathan. “Sounds Like the Mall of America: Programmed Music and the Architectronics of Commerical Space”. Ethnomusicology. 41. 1 (1997): 22-50. Print.

Straw, Will. “Systems of Change, Logics or Articulatoin”. Cultural Studies. 5.3 (1991): 368-388. Print.

Teddy. Personal Interview. 22 Nov. 2013.

Toronto Directory 1861. Metropolitan Toronto Library Canadian History. (1861): 79. 20 Nov. 2013. Print.

Toronto Directory 1862-1863. Metropolitan Toronto Library Canadian History. (1862-1863): 207. 20 Nov. 2013. Print.

Toronto Directory 1929. Metropolitan Toronto Library Canadian History, 8 (1929): 1657. Print.

Toronto Directory 1940. Metropolitan Toronto Library Canadian History, 9 (1940): 391. Print.

Will. Personal Interview. 20 Nov. 2013.