The Masonic Temple: a site analysis

Site description

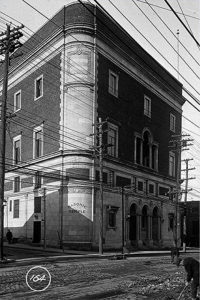

The building currently sitting at 888 Yonge Street, on the northwest corner of Davenport Road and Yonge Street stands empty, although it has had an array of different uses throughout history. It is best known as the Masonic Temple, but has also been identified as The RockPile and The Concert Hall, throughout different musical eras. The six-story buildings’ initial purpose was for it to be used as the Freemasons’ official headquarters. While it experienced many financial difficulties at the time, the Masons began renting out its facility to various music, theatrical and public speaking events as a source of revenue (Skazin, 1999).

History

Designed in the Italian Renaissance Revival Style by architect W.J. Sparling, the six-story structure contains an auditorium that has hardwood flooring and a decorated ceiling. It seats 1200 persons, including the wrap-around gallery. The Masonic Society (Freemasons) included the ballroom/concert hall in their new building and later on began using it as a means to raise revenue from rentals to support the costs of maintaining the building (Skazin, 1999).

John Ross Robertson (1841-1918) was a prominent Mason, and was the founder of the Toronto Telegram newspaper. He was one of the prime motivators behind the construction of the Masonic Temple. When the Masons chose this site, a church was located on the property. After the church was demolished, construction began on November 2, 1916. The final stone for the new Temple was laid on November 17, 1917 and the building was consecrated with corn, oil and wine. The first lodge meeting was held on January 1st 1918. On the upper floors, which were reserved solely for the use of the Masons, there were patterned tiled flooring and many Masonic carvings (Skazin, 1999).

During the 1930s, the Masonic Temple was one of the most popular ballrooms in Toronto; Frank Sinatra even hosted an event. Throughout the years, many famous entertainers have performed in the hall including Tina Turner, The Ramones, and David Bowie (Young, 2002).

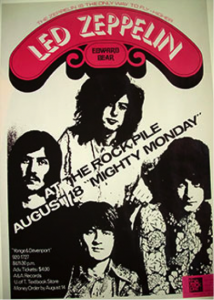

The Temple’s peak came during the late 1960s hallucinogenic era when it was called the Rock Pile. The Rock Pile was famously the scene of two separate 1969 visits by Led Zeppelin, the first in February when the band was virtually unknown and the second in August after the group reached worldwide fame. Before the latter appearance, Zeppelin’s manager extorted a crippling extra fee from the promoters, ultimately bankrupting the Rock Pile, which closed shortly afterwards (Young, 2002).

Although the location remained historically significant and was added to the City of Toronto’s Inventory of Heritage Properties in 1974, the building has changed owners a number of times. The building risked demolition when a developer has planned to build a new high-rise residential building marketed to Asian, because of its “lucky” address at 888 Yonge Street. Luckily, the building was protected under the Ontario Heritage Act that same year and was saved (Friend, 2013).

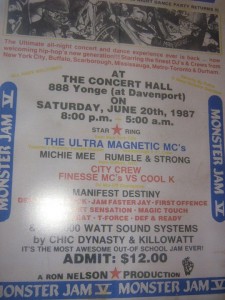

In the 1980s it was best known as the Concert Hall during the very popular hip hop era in Toronto. The Concert Hall was home to many rap battles put on by Ron Nelson Productions (RNP), where he brought talent from New York to battle some of Toronto’s most talented rappers. This was a very significant time for the Concert Hall, but shortly after in the early 90s, Ron Nelson switched his location to the Opera House and the building was left empty. In 1998, the property was sold to CTV, for use as a TV studio to broadcast the show, “Open Mike with Mike Bullard”. In 2006, it became home to Bell Media (MTV), but they too switched locations in 2012. The property was officially listed for sale on March 4, 2013. On June 17, 2013, the Info-Tech Research Group purchased the building for $12.5 million (The Globe and Mail). Info-Tech announced that its plans for the building included staging an annual charity rock concert in the auditorium as a way to conserve the buildings rich musical history.

Site Analysis

For my analysis, I will be focusing on the 1980s to the early 1990s, when the Masonic Temple was best known as the Concert Hall. During this time period, hip-hop and rap were the prominent cultures within its walls. R. Murray Schafer (2009) outlines that a cultural approach is necessary to study the relationship between people and music. Hip-hop culture in Toronto was growing and being heavily influenced by New York’s rap scene. Tricia Rose (1994) emphasized the importance of ‘postindustrial city’ as the main urban influence as providing context for creative development among early hip-hop artists. Toronto, being a city with rich diversity, had a large African American population, who would gather at the rap battles held at the Concert Hall. Post-industrialization had separated different neighborhoods (hoods) within the city and these rap battles were a way of settling beef without any violence involved. My interview held with Trevor, from Top Record Productions, disclosed that the crowds attending the rap battles were predominantly African American. People from every hood of Toronto would convene at the same venue, regardless of what hood they came from. There was the odd fistfight, but that was the extent of it. Unlike today, Caucasians weren’t very present during the rap battles. This outlines two different eras within rap and hip-hop culture. It is evident that different genres of music appealed to different races throughout history, with hip-hop being prominent within black culture during the 80s and early 90s (Foreman, 2000).

Ron Nelson Productions (RNP) hosted most of the events at the Concert Hall as he was always bringing big acts from New York to battle up and coming artists from Toronto (Trevor, 2013). Whether they won or not, there was always a sense of respect and appreciation for the other since they recognized the same struggle and talent needed to battle (Trevor, 2013).

What Cohen (1998) examines on her ethnographic study of the Jewish community in Liverpool, is that music plays a major role in defining one’s identity with their community. Those who share similar tastes in music are likely to unite together. The rap battles at the Concert Hall facilitated that sense of unity within the rap/hip-hop community between people of different hoods and also between battlers from New York and Toronto.

References

Cohen, Sara. “Sounding Out The City: Music and the Sensuous Production of Place.” The Place of Music, Leyshon, A., Matless, D., and Revill, G. (eds), New York: The Guilford Press, 1998. 269-290

Forman, Murray. “Represent: Race, Space and Place in Rap Music.” Popular Music Vol. 19 (2000), No. 1, 65-90.

Friend.D, “Toronto’s historic Masonic Temple sells to consultancy firm for $12.5-million” The Canadian Press. Toronto. Published on June, 17, 2013

Rose, Tricia. 1994. Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America

Schafer, R. M. (1994). The Soundscape. Rochester: Alfred Knopf, Inc.

Skazin. W Paul “The Tale of Two Temples” Volume 22, 1999

Young, P. (2002). Let’s Dance: A Celebration of Ontario’s Dance Halls and Summer Dance Pavilions. Dundurn.

Michie Mee Toronto vs. New York Documentary (Watch last 25% of the video)