THE MIGRATION OF HIPSTERS INTO AUGUSTA AVENUE

THE MIGRATION OF HIPSTERS INTO AUGUSTA AVENUE

Location: Augusta Avenue (north strip)

The following report will examine the history, culture and current descriptions of the north strip of Augusta Avenue. The site analysis will study the ways in which sound and music are used in order to encourage creative activities and experiences, as well as, produce a unique, modern age “hippie” subculture in one of Toronto’s musical landmarks.

HISTORY

The 18th Century

Before exploring Augusta Avenue, this analysis will first examine the history of its surrounding neighborhood – Kensington Market – in order to better understand the effect of popular music on space and culture. Kensington Market refers to the area bounded by College and Dundas Streets, as well as, Bathurst and Spadina Avenue. The history of Kensington Market is of outmost importance in understanding Kensington’s present culture. Historically, before the first European settlers, the market is known to have been inhabited by the First Nations Peoples of Mississauga. The first European settlers arrived in Kensington during the late 18th century, during which the British possessed the land as a part of a massive land sale treaty, first signed in 1787 (St. Stephen’s Community House).

The 19th Century

According to early Toronto archives, after serving in the War of 1812, George Taylor Denison purchased land bounded by Queen St. to the South, Bloor St. to the North, Lippincott the West, and Augusta to the East (Toronto Tourism). The estate was subdivided in the mid 19th century. Small houses were built to accommodate immigrants and laborers, often of Scottish and Irish descent (Toronto Tourism). According to the Kensington Market Historical Society, the initial residents worked as laborers and skilled tradesman, giving Kensington the reputation of an “immigrant reception area” (KMHS).

The 20th Century

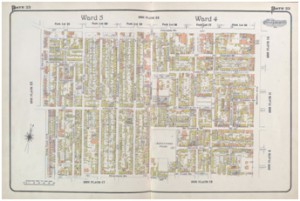

The early 20th Century witnessed a transformation, starting in 1910, when Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe moved into the area. Jewish immigrants occupied what was called “The Ward,” an area between Yonge Street and University Avenue (as seen below in Figure 1). By the end of the 1920’s, the Jews moved out of “The Ward” due to poor living conditions and reestablished themselves in the Kensington neighborhood, forming the largest community of Jews in Toronto. The pre-existing residential area was transformed into a “bustling mixed use residential/commercial hub in the 1910s and 1920” (KMHS). According to the Canadian Encyclopedia, for years, the area was called “The Jewish Market,” as the:

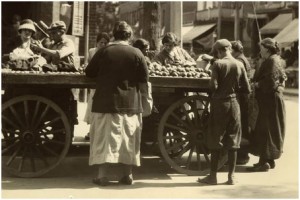

“Jewish merchants sold their wares from pushcarts and horse-drawn wagons, while others converted the first floors of their homes into stores along Kensington Avenue and Baldwin Street, where they sold crated chickens, live fish, pickles and cheeses made on site” (Historica Canada).

This gave the area a unique architectural feature (as seen below in Figure 2).

Moreover, while the 1930’s and 1940’s established Kensington Market as a Jewish community, a rapid demographic shift came following the Second World War (KMHS). Much of the Jewish population, having earned enough money, moved uptown, leaving the market for bigger homes (Toronto Tourism).

Figure 1: Kensington Market exhibited in Ward #4 (1910). Courtesy Toronto Reference Library, Baldwin Room/M912.7135 G57 BR fo.

Figure 2: Kensington Market, circa 1924 (The Jewish Market). Courtesy Toronto Reference Library, Baldwin Room/X-65-64.

Post WWII

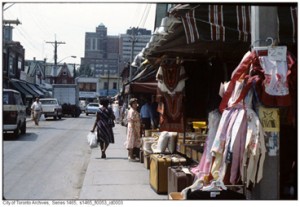

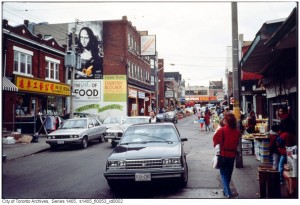

After the Second World War, Portuguese, Brazilian and Hungarian immigrants, as well as, Afro-Canadians replaced the Jewish population. The Kensington Market Historical Society explains that the market allowed the Portuguese immigrants to become a self-sufficient ethnic group with a neighborhood (as seen below in Figure 3), by introducing the neighborhood to: restaurants, bookstores, radio broadcasters, newspapers, a Portuguese bank, real estate brokers, immigration consultants, interpreters, and income tax specialists (KMHS). These new immigrants helped shape the markets vibrant character (as seen below in Figure 4 and 5), as well as, maintain its “outdoor market, interior milieu of vintage and ethnic stores and unique pedestrian environment” (KMHS).

Furthermore, the 1970’s and 1980’s witnessed several shifts in terms of immigration and marketplace culture, as a rapid demographic of East and Southeast Asian and Caribbean immigrants settled into Kensington market (KMHS). Another change occurred throughout the 1980’s and 1990’s when “Bohemian merchants and young urban professionals settled and established businesses and galleries in the Market” (KMHS). This new development in immigrant entrepreneurism and bohemian culture, gave way to Kensington Market as an important part of pop culture. Kensington markets unique culture is most notably depicted in King of Kensington, a CBC television sitcom, as well as, CBC’s Tuning in, which celebrated the markets ethnic diversity and entrepreneurial spirit which has survived in the community until this day (KMHS).

Kensington Market Today

The market today has a combination of both residential and commercial buildings. The commercial buildings typically include vintage and ethnic stores (KMHS). Moreover, to draw in more residents and tourists, the area has created Pedestrian Sundays, where parts of Augusta Street, Baldwin Street and Kensington Avenue are closed to motorized vehicles. The festival allows live music, dancing and street theater to encompass the market. Interestingly, the neighborhood demographic has changed once again, housing youth between the ages of fifteen to twenty-four (KMHS). According to Toronto archives, these youth tend to be writers, artists, and college students who have kept the Bohemian element in their predominantly working- class, immigrant neighborhood (Toronto Tourism).

DESCRIPTION OF THE SITE

This site description will examine the north strip of Augusta Avenue in Kensington Market, as it is an important location to the neighborhoods festival, “Pedestrian Sundays”. Turning south onto Augusta, the east side of the street turns into a stage where bands are welcome to perform during the festival. The west side of Augusta (which is intended to be concrete steps,) turns into a sitting area for audiences. As the festival closes off roads to all motorized vehicles, the road functions as a dance floor, allowing the audience to co-exist together in the community and enjoy its music. There are no media on the site (with the exception of street lamps), and all speakers and monitors are placed on the east side of Augusta where the band performs. Further along the strip, are vibrantly colored commercial sites that specialize in vintage clothing, ethnic foods and cannabis cafes. The mediums in these commercial spaces are speakers placed indoors that at times project indie or alternative music onto the street.

SITE ANALYSIS

The following site analysis concentrates on the north strip of Augusta Avenue in Kensington Market in order to explore the way in which music is used at the site to produce a culture based on age, class and drugs. While music is an important element to the north strip of Augusta’s subculture, other sites on Augusta Avenue will be referenced to further explain the creative experiences and activities that Augusta Avenue encourages.

First, it is important to note that Augusta Avenue changed from a residential neighborhood to a commercial neighborhood; however, as witnessed in the history above, the neighborhood is still predominantly a working- class immigrant neighborhood. Additionally, Augusta Avenue is well known for its vibrant commercial buildings, which are often covered in concert posters and graffiti (as seen in Figure #6). The strip is always open to inviting oncoming pedestrians to enjoy the site and its music. Augusta Avenue is also credited with a Bohemian element (as witnessed by the colorful murals on buildings), which is attributed to the youth that reside in the neighborhood who tend to be college students interested in the arts (Toronto Tourism).

Figure #6: Graffiti on Augusta AVenue. (Cosco, Amanda. GRAFFITI KENSINGTON MARKET TORONTO. 2012. Photograph. Girl About Toronto, Toronto. Web. 3 Dec 2013.)

Moreover, looking at Augusta through a semiotic lens, we see the youth residing on the site as part of the modern age “hippie” subculture. Cultural Theorist Paul Willis first applied the term “homology” to the hippie subculture, using it to “describe the symbolic fit between the values and life-styles of a group, its subjective experience and the music forms it uses to reinforce its focal concern” (Hebdige 56). For instance, Willis suggests that hallucinogenic drugs and acid rock made the hippie culture come together. In this way, there is a homological relationship between the vintage bohemian clothes (Bungalow located in 273 Augusta), cannabis consumption (The Hot Box Café 204 Augusta), interest in art and Jazz (Poetry Jazz Café 224 Augusta), independent music (Pedestrian Sunday’s along Augusta Avenue), and Augusta’s “hipster” subculture.

Drawing on Willis’ analysis, the hipster youth mirror the hippie subculture, as conflicts of social dominance are what drive communities whose members are regarded as hipsters. According to a long time street performer at the intersection of College Street and Augusta Avenue, “the Kensington Market neighborhood is full of hipsters. Most of the people who work around here are hipsters, although, many of them are just on their way to OCAD” (Personal Interview 1). Assistant Professor at New School University, Mark Greif, suggests that hipsters are often lower-middle class youth, living in the urban core and often working poor jobs. Only on the basis of their “cool” clothes and alternative taste in music can they be superior: “hipster knowledge compensates for economic immobility” (Greif BR27).

The above interpretation suggests that economic position defines musical expression. Therefore, the lower-class hipster subculture of Augusta Avenue is linked to a “Do It Yourself” culture, which favors independent music, such as that on Pedestrian Sunday’s. This represents music as a way of projecting identity outward, suggesting Brandon LaBelle’s theory of auditory scuffle: projecting our ability to latch on to sounds outwards (LaBelle 187). For example, independent music favors the “do-it-yourself” approach, where “music is written, recorded and distributed independently,” suggests Daniel, who has worked on Augusta Avenue for over two years and has over eleven years of experience in the Canadian music industry (Personal Interview 2). According to Murray Schafer, the independent music on Augusta Avenue hints at a relationship between “man and the sounds of his environment”. Therefore, there is a direct correlation between the sound produced and the space in which it is heard. For instance, the lower-class youth of Augusta favor an independent approach to making music, as it is in their price range, just as they favor a non-mainstream fashion approach (vintage, thrift store and home-made clothing), as well as other forms of self-expression (such as art and poetry). The sound becomes synonymous with the space, as a community is produced around the independent “do- it – yourself” music and culture.

With the above economic structure, Augusta’s relationship to independent music attracts a younger lower-class audience. Thus suggesting what Graham St John entitles a “scene” in the Augusta Avenue community (as seen in Figure #7). St John explains that by affiliating with a scene (such as the independent music scene), one must associate and infuse their identity with that scene (St John 41). In this respect, the independent music scene in Augusta produces a subculture connected through independent music, non–mainstream fashion, and drugs as a distinguishable feature of their self- identity. Sara Cohen, in “Sounding Out the City” agrees with St John, suggesting that the way music is used, defines and distinguishes people and places according to class and identity; in this way, there are authentic traces of identity in music (Cohen 273). Class and identity are reflected in Augusta Avenues independent music culture, as the approach to making music is raw and experimental, often suggesting a younger lower-class feel. Thus, a community with a similar sense of identity and meaning is produced. In contrast, those of older stature, higher – class, and different interests and values, are excluded from the site, as they are not affiliated with Augusta’s “scene”.

Figure #7: Subculture forms during “Pedestrian Sunday”. (Grut, Nicolai . Pedestrian Sundays in Toronto’s Kensington Market. 2009. Photograph. Flickr, Toronto . Web. 3 Dec 2013.)

This segregation of space is reflected in Lily E. Hirsch’s article entitled “Weaponizing Classical Music,” which examines the use of classical music in businesses in order to control and repel teens (Hirsch 342). Hirsh explains that classical music is “successful not in elevating or rehabilitating hooligans, but in chasing them away” (Hirsch 348). In this regard, loud alternative music becomes part of Augusta Avenue’s soundscape, discouraging adult activities, and in extension, “chasing them away”. Additionally, the “Pedestrian Sunday Festival,” is important for analyzing the way in which music encompasses space. According to Cohen, the “consumption and production of music also draws people together and symbolizes their sense of collectivity and place” (Cohen 273). In this manner, the music played during the festival brings forth a community with a similar sense of space and place.

Furthermore, Augusta’s “space” is known for its indulgence of drug culture, as Augusta is home to one of Canada’s few cannabis cafes, where the consumption of cannabis takes place openly (The Hot Box Café/Roach’o’Rama 204 Augusta Ave, seen below in Figure #8.) The Hot Box Café encourages youth to participate in drug culture while partaking in alternative music experiences, such as the “Pedestrian Sundays Festival”. Simon Reynold, who discusses the “Hardcore Continuum,” suggests that drugs are an important part of the musical experience. The way the body moves and understands sounds is often due to the effects of drugs, as it is “about tapping into people’s innards” (Reynold). Brandon Labelle explains that dancing is a form of “auditory latching,” as the body attaches itself to sound. For instance, according to Daniel, when the road during Pedestrian Sunday’s turns into a dance floor, “people on the streets are always dancing, grooving to the music, clapping and yelling to songs. The people here are just looking for a good time: relaxing, getting high and listening to some good tunes” (Personal Interview 2). This suggests that the music in Augusta Avenue encourages “auditory latching,” as physical reactions (such as dancing) almost become subconscious. Additionally, as Daniel suggest, the music on Augusta is often enhanced by drug culture, further extending the homological relationship between drugs, independent music and lower – class youth.

Figure #8: Hot Box Cafe/ Roach – O – Rama (Figure 8: Flack, Derek. Hot Box Cafe to become lounge at Roach-O-Rama. 2012. Photograph. BlogTo, Toronto. Web. 3 Dec 2013.)

Due to this, Augusta’s unique Bohemian culture is the reason for the sites popular music and Pedestrian Sunday’s festival. By closing off the roads to motorized vehicles and opening up the site to oncoming pedestrians, Augusta becomes a dance floor where Kensington’s creative culture is encouraged. To conclude, Augusta Avenue produces a modern “hippie” subculture that is based on class, age and drugs. Alternative and Independent music is used at the site to encourage creative activities and experiences, such as, dancing and cannabis consumption. By producing a community that shares similar meanings, authentic traces of identity are left in the music performed. In this way, Augusta Avenue becomes a “scene” within one of Toronto’s many musical landmarks.

REFERENCES

Canada. Toronto Tourism. Kensington Avenue . Toronto: Toronto Archives, Web.<http://Toronto Tourism.ca/inter/trans/towalktours.nsf/Toronto_Walking_Tour-Kensington_Market.pdf>.

Cohen, Sara. “Sounding Out the City: Music and the Sensuous Production of Place.” Array. The Place of Music. New York : The Guilford Press, 1988. 269 – 290. Web. 2 Dec. 2013.

Greif, Mark. “The Hipster in the Mirror.” New York Times 14 11 2010, Sunday Book Review BR27. Print.

Hebdige, Dick. “Signifying Practice.” Trans. Array Subculture: The Meaning of Style. London: 1979. Web. 2 Dec. 2013.

Hirsch, Lily. “Weaponizing Classical Music: Crime Prevention and Symbolic Power in the Age of Repetition.” Journal of Popular Music Studies. 19.4 (2007): 342 – 358. Web. 2 Dec. 2013.

Historica Canada . “Kensington Avenue .” The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Web. 27 Nov 2013. <http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/articles/toronto-feature-kensington-market>.

KMHS. “Kensington Market Historical Society .” KMHS. KMHS, Web. 27 Nov 2013. <http://www.kmhs.ca/about-us/>.

LaBelle, Brandon. “Pump up the bass – rhythm, cars, and auditory scaffolding.” Senses & Society. 3.2 (2008): 187 – 204. Web. 2 Dec. 2013.

Reynolds, Simon. “Above The Treeline.” Wire. Sep 1994: n. page. Web. 2 Dec. 2013.

Schafer, Murray . The Soundscape. ‘Introduction’ and ‘Listening’. Destiny Books, 1994. 3 – 12. Web.

St John, Graham . “Neotrance and the Psychedelic Festival.”Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Culture. 1.2 (2009): 35 – 64. Web. 2 Dec. 2013.

St. Stephen’s Community House. “Kensington Alive.”Ststephenshouse. St. Stephen’s Community House, Web. 27 Nov 2013. <http://www.ststephenshouse.com/kensingtonalive/index1.html>.